Research on Hibernation?

RIKEN BDR researchers are carrying out many intriguing and interesting research projects, but it can sometimes be difficult to understand what they are actually doing.

Coordinator Hideki meets with researchers to delve behind the scenes of their research.

Hideki’s interest was piqued when he heard that special postdoctoral researcher Genshiro Sunagawa is conducting research related to hibernation. His first impression of Sunagawa was that he looked a bit intimidating…

For safer emergency transportation

I’ve heard that your research theme is hibernation. Can I ask you, why hibernation?

Now, I am a researcher but I started my career as a pediatrician. When I was working at the National Center for Child Health and Development (NCCHD), I saw many cases where a patient could not be transported due to the severity of their condition. In fact, transporting a patient can sometimes be troublesome by affecting their condition as well.

In what kind of situations is transportation difficult?

Patients are attached to tubes and a ventilator, and are under anesthesia. In this condition, even small bumps during transportation could put a heavy load on the heart. In worst cases, it will kill the patient, unfortunately. I had been thinking how we can transport those severe patients more safely. Tell you the truth, I didn’t think of hibernation at the beginning.

The fateful encounter

I came across a paper entitled, “Hibernation of monkeys,” just after finishing an overnight shift. I will never forget that moment. It was in 2005. My initial thought after reading it was, “this can be applied to humans as well!” I was so moved by the paper, although this feeling may have been caused by fatigue from working overnight. I decided that year to enter graduate school.

Indeed, it sounds like a fateful encounter.

Yes, it was. By the way, I was mainly specializing in anesthesiology at NCCHD.

Aren’t there many anesthetists at such a large hospital?

Of course. But working in ICU requires much knowledge and skills of anesthetization. Once I realized this, I mainly focused on anesthesiology. I worked on hundreds of cases, even though I was only there for two years. This experience is what led me to hibernation research. I will never forget that paper.

Oh, and one more interesting thing was that monkey lived in Madagascar.

Wait. Madagascar is located on the east side of Africa. Monkeys hibernate even in a such tropical area?

Yes. This was one of the most interesting points in that paper, though I didn’t realize it at the time.

What exactly is hibernation?

Can you explain what hibernation means?

Recently, hibernation is said to be a survival strategy for animals in which they can lower their metabolism under conditions where energy intake is difficult. Winter is the typical situation, but it is not limited to winter. Even mice can enter this mode after starvation.

That’s an amazing ability when you think about it. And mice can enter hibernation mode just by starvation?

Yes, although it doesn’t happen right away.

We, animals, have a system for maintaining body temperature at 37°C, which is amazing because it’s difficult to maintain that temperature. It’s like an air conditioner.

It is easier to maintain body temperature in larger body masses than smaller body masses. Elephants and bears can retain body heat only by producing small amount of heat.

Is that true?

Yes. Oxygen consumption per unit mass of an elephant is equivalent to that of a squirrel in hibernation mode. Interesting, isn’t it?

No brain waves even if the animal is still alive!?

Is there some sort of special trick with the model mice you are using, like genetic modification?

No, we are actually using mouse lines commonly used in research. They are not even a hibernation model. But they can enter hibernation state after starving them for 24 hours with body temperatures dropping to 20°C from 37°C.

Body temperatures of hibernating animals like squirrels, dormice, and hamsters drop to below 10°C. These hibernating animals also start generating heat once external temperature falls too low. This means that at least some part of the autonomic nervous system remains active. But interestingly no significant brain waves are detected in this state.

So, is it possible to look at brain waves of mice?

Yes, it’s fairly easy. But I really want to look at those in hibernating animals. It would be fascinating if they could sense external temperatures in an area of the body besides the brain.

What was the link between anesthesiology and hibernation?

I still don’t understand why you thought, “This is it!” when you read the monkey hibernation paper.

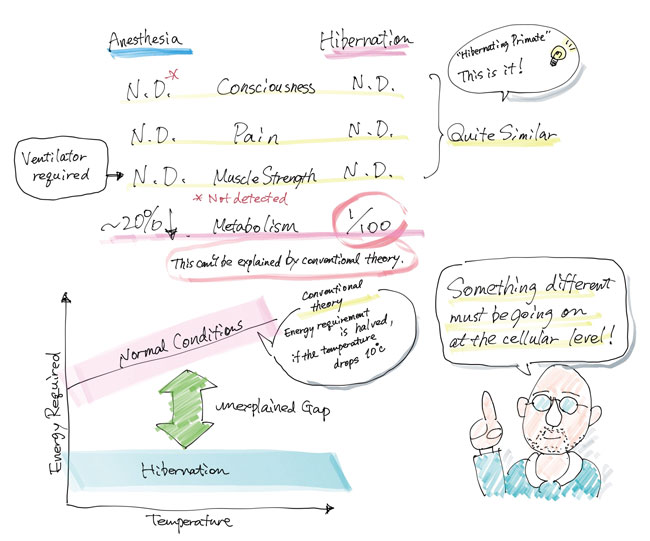

I see. Let me start by explaining the differences between anesthetization and hibernation. Anesthetization is used to stop three functions during surgery. First is consciousness because, as you know, surgery is painful. Second is feeling pain, as pain places stress on the body even when unconscious. The last one is muscle strength, since it’s dangerous if a patient moves during surgery. But this leads to one problem, which is once muscle function is lost, breathing also stops. Therefore, a mechanical ventilator is required. This is what we call general anesthesia.

In hibernation, consciousness is likely lost. The animal also likely does not feel pain as there are no detectable brain waves, though we don’t know quite well about it. They also lack muscle strength since the body is limp. So, you can see anesthesia and hibernation are quite similar.

When a patient is anesthetized, it means that you are reducing the body’s energy requirement—only around a 10 to 20% reduction, though. But, in some hibernating animals, their basal metabolism can drop to 1%, meaning, in theory, the heart only needs to work 1/100 of normal capacity.

Wow, that’s an astonishing difference!

Chemical reactions unfolding in the cells of hibernating animals are likely different from non-hibernating ones.

Hibernation needs to be understood at the cellular scale

What do you mean by saying the chemical reactions are different?

From a chemistry perspective, if the temperature drops 10°C, energy requirements should also drop to about half. If the temperature drops 30°C, theoretically energy requirements fall to one-tenth to one-eighth of normal conditions, meaning oxygen consumption should also be within this range.

In reality, oxygen consumption drops down to 1/100 of normal conditions in hibernating animals. This observation cannot be explained with conventional knowledge, so something different must be taking place. That is what I really want to know.

So, you are going to address it using a cellular approach, then?

Hibernation is basically linked to metabolism, so I think it’s possible to address at the cellular level. This way we can also apply it to human iPS cells and advance research in that arena. I plan to work toward realizing my dreams for hibernation research, and RIKEN’s research facilities offers a great environment for advancing research.

I didn’t realize the breadth of hibernation research. Thank you for sharing your intriguing research.

POSTSCRIPT

He looked a little rough at first glance, but as our conversation unfolded, his soft-spoken and friendly demeanor made me quickly realize that he is a really nice guy and I could easily picture him as a pediatrician. He can take difficult concepts and break them down into simple terms. Hibernation research is a catchy theme, but I couldn’t see the link between anesthesiology and hibernation at first. After talking to him, I think I understand what drives his research—medical innovation.