A Step-by-step Approach to Aging Research

This time, I interview research scientist Masaharu Uno. I heard that his research was on aging using worms. Why worms, I wondered as I made my way to go talk to him.

Aging research using worms

First of all, can you tell me what your research theme is?

I am looking at organismal aging and response to environmental stimulus using the C. elegans worm.

The external environment is continuously changing during an organism’s lifespan. And all living animals need to adapt to environmental changes such as temperature and the amount of food available. I’m looking at how these factors affect the lifespan (of worms).

From a layman’s perspective, humans and worms appear to be very different.

There are of course many differences, but there are also many points that are conserved between humans and worms. In fact, many genes have been found conserved in both worms and mammals. Thus, I think we can apply our findings from worms to humans.

Why did you choose aging as your research theme?

You and I can consider our bodies to be matured. So naturally, the immediate question would be what will unfold next. Don’t you find it mystifying that even though we were born into this world, we all have to die? Wouldn’t it be fantastic if we could answer this question?

I think from an evolutionary perspective, people used to view aging as a process that was not strictly regulated. This is because evolution is considered to be a phenomenon in which there is a bias toward ensuring the survival of more offspring. Aging is a process that takes place after the reproductive period, so it can be thought that evolution would not select for extending individual lifespans. As aging is also thought to be just a process in which the physical body deteriorates, it’s hard to think there is some system regulating this process.

I see your point. How are you trying to examine this, then?

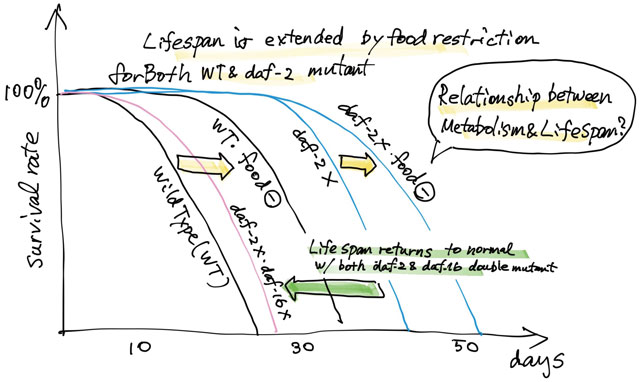

For example, there is a gene called daf-2, and when there is a mutation in this gene, we can observe a doubled lifespan. Downstream of DAF-2, there is a signaling cascade where DAF-16 functions. If you generate a worm with a mutation for both daf-2 and daf-16, the lifespan returns to normal. DAF-2 is a receptor for growth factor IGF-1, and DAF-16 is conserved as transcription factor FOXO in mammals. So we are trying to search for factors regulating aging by using lifespan as an indicator.

Relation between life span and metabolism

You mentioned something earlier about the amount of food, right?

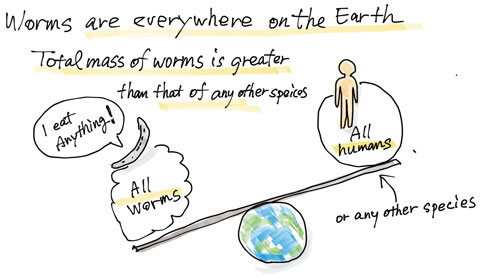

Worms can be found all over the world, and some say that the total mass of all worms on Earth is greater than any other species on this planet. They can feed on almost anything. We breed them with colon bacillus (E. coli), but some researchers are known to feed them dog food. They can also eat wood.

I recall reading a news story about eliminating worms from farms and golf courses.

They eat pretty much anything, and will continuously feed if there is food present. But it’s well known that their lifespan almost doubles when food is restricted. I’m now trying to examine the relationship between genetic background and food restriction.

They eat pretty much anything, and will continuously feed if there is food present. But it’s well known that their lifespan almost doubles when food is restricted. I’m now trying to examine the relationship between genetic background and food restriction.

Do you remember I mentioned that the daf-2 mutant has a doubled lifespan? Well, although you can extend it even further with food restriction, the extent of the lifespan extension in daf-2 mutants by food restriction is smaller than that observed in wild type.

The daf-2 is a homolog of the Insulin/IGF-1 receptor. IGF-1 is Insulin-like growth factor-1. This suggests that lifespan regulation by food restriction might involve insulin and the IGF-1 signaling pathway, and also leads us to hypothesize that there is a link between lifespan and metabolism.

Are there any other environmental factors that you are applying to worms?

We sometimes use arsenic and hydrogen peroxide solution to place them under oxidative stress, and sometimes use osmotic pressure.

How do you apply osmotic pressure?

This can be done by raising the salinity of the breeding environment. This is kind of interesting, since we have observed that worms bred under conditions of mild stress can acquire greater resistance to lethal stress.

So if worms have been bred in low food environment, does that mean they can live much longer if they run out of food?

Actually, it’s not that straightforward. Worms can actually survive for a long time without food.

Wait, but didn’t you say that worms eat anything and that the lifespan of worms is about one month?

Yes, I did say that, but it’s a bit more complicated than that. If placed under food restriction during early development, worms will enter a state called dauer, which enables them to survive about three months. The body is covered with a hard cuticle layer and becomes more resistant to environmental stress. When food becomes available, they exit the daur state and resume development.

They can sense food nearby even when enclosed in that shell? How greedy they are!

They can detect foods by smell using sensory neurons that are protrude outside of the cuticle layer. Do you know that a technology is being developed to use worms to detect early-stage cancers? That is how sensitive the olfactory senses of worms are, and some say it is greater than that of dogs.

Research steadily, one step at a time

Was aging research your interest from the beginning?

To be honest, I wasn’t thinking of using worms to study aging when I was a student. I found the work of the many senior researchers in my lab at Kyoto University to be very fascinating, and that was what made me want to give it a try. And before I knew it, I had also decided to become a researcher. I think that the lab environment was good for me.

BDR is also now a good environment for me, since there are many researchers here working in diverse areas, from development, regeneration and structural biology to AI and mathematical modeling. I really do enjoy the different seminars held at BDR.

That is good to hear. It also sounds like you are getting some new ideas?

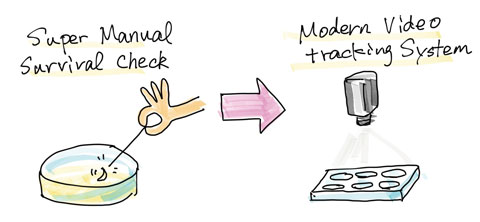

That’s right! We use a thin platinum wire to check if a worm is alive or dead. If the worm moves when you poke it, it’s alive. If it doesn’t move, then it’s dead. On a good day, I can check about 1,000 worms using this manual method, but this is not very efficient, right? So, I am now starting to discuss with other researchers about trying to develop a new system to check this by taking daily photos and analyzing the images.

Wow, so the super labor-intensive method is now going to be sophisticated.

This will be really good since worms are transparent and taking photos will give us further information about their internal organs, like a CT scan. We can also track changes in their bodies from day to day. I believe this will help us to see other features of aging that we haven’t seen yet.

What kind of things?

One of the difficulties of aging research is the huge differences among individuals.

For instance, imagine that we have 10-day old worms. Some might live five more days, and others maybe ten more days. Now we have them grouped based on when they were born, but we can’t tell how long they will live. This is also true for humans–having the same birthday does not mean they will die on the same day. Once we can predict remaining life expectancy, we might be able to see something much different. This is still under discussion, though.

It seems like you have a long road ahead.

Aging involves many factors like diet, genetic background and individual differences. I don’t think we can jump straight away into research using higher living organisms such as mice and humans. What we have found so far may only be happening in a particular stage of life. Capturing daily images will be the first step toward grasping the process of aging. For now, I’m focusing on trying to fully understand aging in worms.

I see. Steadily and step by step.

POSTSCRIPT

I found it impressive that he aspired to become researcher because he was awestruck by the researchers around him. The ability to find something interesting, even if it has no direct relation to his/her own research, may be the key to making new discoveries. His step-by-step approach also left a deep impression on me, since many people, including myself, tend to try and leap to the goal.